Holy Gospel of Jesus Christ according to Saint Mark 1:21-28.

Then they came to Capernaum, and on the sabbath Jesus entered the synagogue and taught.

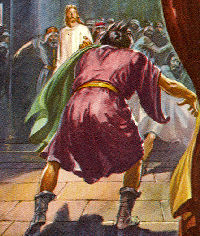

The people were astonished at his teaching, for he taught them as one having authority and not as the scribes. In their synagogue was a man with an unclean spirit; he cried out, “What have you to do with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are–the Holy One of God!” Jesus rebuked him and said, “Quiet! Come out of him!”

The unclean spirit convulsed him and with a loud cry came out of him.

All were amazed and asked one another, “What is this? A new teaching with authority. He commands even the unclean spirits and they obey him.”

His fame spread everywhere throughout the whole region of Galilee.

February 1st 2015The people were astonished at his teaching, for he taught them as one having authority and not as the scribes. In their synagogue was a man with an unclean spirit; he cried out, “What have you to do with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are–the Holy One of God!” Jesus rebuked him and said, “Quiet! Come out of him!”

The unclean spirit convulsed him and with a loud cry came out of him.

All were amazed and asked one another, “What is this? A new teaching with authority. He commands even the unclean spirits and they obey him.”

His fame spread everywhere throughout the whole region of Galilee.

Sunday, Mass Homily,

Ordinary Time: February 1st

Fourth Sunday of Ordinary Time

Old Calendar: Septuagesima Sunday

In their synagogue was a man with an unclean spirit; he cried out, "What have you to do with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are—the Holy One of God!" Jesus rebuked him and said, "Quiet! Come out of him!" The unclean spirit convulsed him and with a loud cry came out of him (Mark 1:23-26).

Sunday Readings

The first reading is taken from the Book of Deuteronomy 18:15-20. This central section of this book describes the various offices and officers of the theocratic society which Yahweh, through his servant Moses, is setting up for the Chosen People.

The first reading is taken from the Book of Deuteronomy 18:15-20. This central section of this book describes the various offices and officers of the theocratic society which Yahweh, through his servant Moses, is setting up for the Chosen People.

The second reading is from the first Letter of St. Paul to the Corinthians 7:32-35. He devotes chapter 7 to answering questions concerning marriage and virginity. In today's extract he emphasizes freedom to serve God fully, freedom from earthly cares which those who choose a life of celibacy have.

The Gospel is from St. Mark 1:21-28. St. Mark makes it clear that, from the very first day of Christ's public ministry, his messianic power began to be manifested to those who saw and heard him. The Jews of Capernaum were "astonished" at his teaching and "amazed" at his power over the evil spirits. "What is this," they asked one another, "a new teaching and the unclean spirits obey him!" But they were still a long way from recognizing him for what he was, the Messiah and Son of God. This is as might be expected, the astounding mystery of the incarnation was way beyond human expectation or human imagination. And it was our Lord's own plan to reveal this mystery, slowly and gradually, so that when the chain of evidence had been completed by his resurrection, his followers could look back and see each link in that chain. Then they would be ready to accept without hesitation the mystery of the incarnation and realize the infinite love and power of God that brought it about. We look back today through the eyes of the Evangelists, and, like them, know that Christ was God as well as man—two natures in one person. We should not therefore be "amazed" at the teaching of Jesus or at his power over the unclean spirits. What should amaze us really is the love that God showed mankind in becoming one of our race.

We are creatures with nothing of our own to boast of. We were created by God, and every talent or power we possess was given us by God. God's benevolence could have stopped there and we would have no right to complain. But when we recall the special gifts he gave man, which raise him above all other created things, we see that he could not, because of his own infinitely benevolent nature, leave us to an earthly fate. What thinking man could be content with a short span of life on earth? What real purpose in life could an intelligent being have who knew that nothing awaited him but eternal oblivion in the grave? What fulfillment would man's intellectual faculties find in a few years of what is for the majority of people perpetual struggle for earthly survival? No, God created us to elevate us, after our earthly sojourn, to an eternal existence where all our desires and potentialities would have their true fulfillment. Hence the incarnation, hence the life, death and resurrection of Christ, who was God's Son, as the central turning point of man's history.

Today, while amazed at God's love for us, let us also be justly amazed at the shabby and grudging return we make for love. Many amongst us even deny that act of God's infinite love, not from convincing historical and logical proofs, but in order to justify their own unwillingness to co-operate with the divine plan for their eternal future. This is not to say that their future, after death, does not concern them; it is a thought which time and again intrudes on all men, but they have allowed the affairs of this world which should be stepping stones to their future life, to become instead mill-stones which crush their spirits and their own true self-interests.

While we sincerely hope that we are not in that class, we can still find many facets in our daily Christian lives which can and should make us amazed at our lack of gratitude to God and to his incarnate Son. 'Leaving out serious sin which turns us away from God if not against him, how warm is our charity, our love of God and neighbor? How much of our time do we give to the things of God and how much to the things of Caesar? How often does our daily struggle for earthly existence and the grumbles and grouses which it causes, blot out from our view the eternal purpose God had in giving us this earthly existence. How often during the past year have we said from our heart: "Thank you, God, for putting me in this world, and thank you a thousand times more, for giving me the opportunity and the means of reaching the next world where I shall live happily for evermore in your presence"? If the true answer for many of us is "not once," then begin today. Let us say it now with all sincerity, and say it often in the years that are left to us.

— Excerpted from The Sunday Readings by Fr. Kevin O'Sullivan, O.F.M.

Commentary for the Readings in the Extraordinary Form:

Septuagesima Sunday

"Why do you stand here all day idle? . . . Go you also into the vineyard" (Gospel).

"Why do you stand here all day idle? . . . Go you also into the vineyard" (Gospel).

Septuagesima Sunday

"Why do you stand here all day idle? . . . Go you also into the vineyard" (Gospel).

"Why do you stand here all day idle? . . . Go you also into the vineyard" (Gospel).

As athletes of Christ we are called to a competitive "race" (Epistle). As workers with Christ we are ordered into the "vineyard" (Gospel).

It is a "race" with death for the "prize" of life eternal. Only "one receives the prize" by His own right, Christ! But, remember, He still runs in us if we do not lag in this "race," as did Israel under "Moses" (Epistle).

God comes to us "early" in life. Unitl the last "hour" He repeats, "Why . . . stand . . . idle?" Each "hour" brings us nearer to the "evening" of reward, not due to the excellence of our work in itself but mercifully given by God as a recompense (Gospel).

— Excerpted from My Sunday Missal, Confraternity of the Precious Blood

| Video |

Sunday, February 1st. Holy Gospel of Jesus Christ according to St Mark 1:21-28.