|

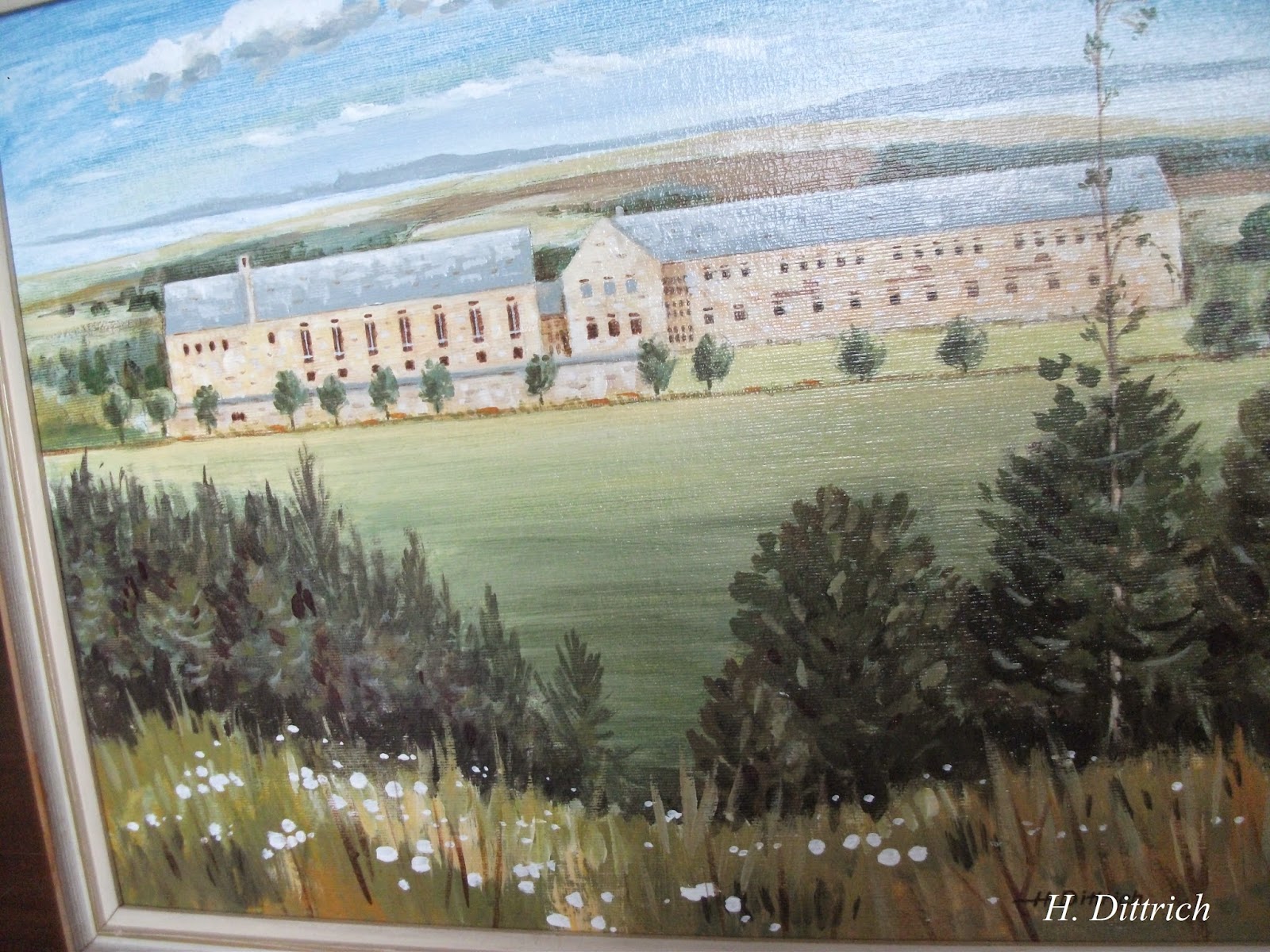

Devotion: Father Mark, left, main picture, and fellow monks in the Abbey grounds.

Above, writer Kevin McKenna joins them in prayer.

|

AFTER too many years where willingly you became imprisoned in ceaseless noise and exclamation the silence you first encounter in a living Cistercian monastery is quite, quite shocking. And then, at last, when your senses become accustomed to the slower heartbeat of this place a sort of liberation occurs and you begin to catch the echo of something long concealed but never quite forgotten. There is peace here but you are troubled just the same.

Nunraw Abbey lies 20 miles or so from Edinburgh, near the ancient burgh of Haddington in the midst of the Lammermuir Hills. These fells are gentle in the summer but now, at the onset of winter, have become moody and the isolation in this stone fastness becomes profound. The abbey and its quadrangles, built over a 17-year period from 1952 by volunteer labour from parishes all over Scotland, once quietly resonated to the chants and cadences of about 60 Cistercian Trappist monks. Now only 12 are left, all elderly and all waiting to see if their numbers will be swelled by other men similarly seeking the presence of God in the silence and, perhaps, His voice; the call of the mild.

Once, a long time ago, I came here during student days when my Christian faith was still constant and unmitigated but already beginning to fray with exposure to the blandishments of a world which rebuked spirituality and reviled all that could not be touched or safely predicted. Along the way there were oases of belief amongst good people but too often these were diminished by their terrifying certainty about a world in which all I could see was glorious uncertainty and perfect doubt.

Now I am desperately clinging to the remnants of faith after 30 years in a fast and loud industry where contemplation is held captive by the tyranny of the here and now. I’m not sure what I was searching for then and, 30 years later, I’m still unsure but almost fearful now at what has brought me back here.

These monks follow the strict Rule of St Benedict, a daily and austere regime of prayer, spiritual exercise and manual labour which was set down almost 1,000 years ago. In a world where the constant striving for material advantage has wrought war and widespread inequality you could reasonably ask of what relevance is a life of such devotion to something invisible and seemingly intangible.

I AM still asking myself this when I rise at 3am to prepare for vigils. I reflect that the last time I saw this hour was in the company of some brazen cocktails and loud blues music in one of Glasgow’s edgier nightclubs. I am also reflecting that my day will end at 8pm and follow a strict agenda which would make Mahatma Gandhi look like a slacker.

As well as vigils there is Angelus, Lauds, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers and Compline; all of these being the sung psalms and responses of the ancient Church which in turn praise, thank and entreat God. During these spiritual interludes the monks line up in wooden stalls – six on either side of the chapel – facing each other and singing the psalms in faltering and wispy voices. I have been accorded the rare privilege of joining them and, feeling bewildered and self-conscious in jumper and jeans, I bow and genuflect in the wrong places amidst a mosaic of white and black habits. And gradually the cause and purpose of their day and this life begins slowly and silently to reveal itself.

The previous day I had been welcomed by Father Mark Caira, Abbot of Nunraw, who leads this community. He is a fit and youthful man in his mid70s who doesn’t look old enough to have collected his bus pass and whose laughing eyes belie a lifetime of austerity and spiritual devotion. He is from Airdrie, Lanarkshire, originally and soon we are talking of the independence referendum, a topic which has replaced football as the icebreaker when men from the West of Scotland first encounter each other.

‘We all voted that day,’ he says. ‘But I don’t know what the split was among the community, it wasn’t really discussed much.

‘Recently I attended an annual international gathering of our Order in Assisi and it seemed that all my international brethren wanted to discuss it. Every one of them, it seemed, had a comment to make about it.’

Soon though, we are talking about silence and the idea of God in a world that has never seemed so far away from concepts of spirituality and the divine. ‘We have all the essentials of life here and we’re not over-pious, but gradually you come to understand that God doesn’t reveal Himself until you are quiet enough to listen.’

Last year, the monks were forced to sell the 16th century tower adjoining the abbey which has served as their guest-house. Lately, the work of maintaining it had simply become too onerous for a community diminishing in numbers and advancing in age. A smaller guest facility is under construction within the main building.

Quiet little miracles occurred in the old building, attested to by generations of those who visited. There are abundant tales of people, wounded and broken by separation, violence, drugs and alcohol who found healing at Nunraw and an epiphany.

‘They come here and can gain an insight into their own needs,’ says Father Mark. ‘Some seem surprised that we haven’t taken a vow of silence. Instead of that I like to think we have taken a vow of stability here and that there is instead a spirit of silence.’

He has been at Nunraw for almost 50 years: ‘I believe I was led here and if

this happens you have to be true to yourself. This isn’t prison; it’s hard to enter and easy to leave.’

These monks are almost entirely self-sufficient, having become adept at farming they adhere rigorously to a vegetarian diet and eat daily the produce of their own soil. On special commemorative days they will allow themselves some meat. Christmas Day is one such occasion, of course, and so some of the rituals will be observed.

Already there are Christmas cards gathering on a table and, on the Saviour’s day itself, there may be telephone calls to close relatives. Otherwise though, the rhythm and cadences of their day will remain unaltered. What f ew bills and expenses they incur are met with the help of gifts and donations from a wider community of Nunraw friends and relatives stretching throughout the Scottish diaspora.

It’s during meal times that you first encounter proper silence. The first minutes you experience in a dining hall where these 12 are seated two to a table, eating their food with no conversation are unnerving. And then you gradually grow accustomed to it and are glad of it; no requirement for empty speculation and idle wit – just you and your food and thoughts about where it came from and how fortunate you are that it is always here. And thoughts, too, of those many among us who must live in hunger or in the fog of war. And then you find your own absorption in shallow concerns ebbing away.

The story is told of a harsh winter in these parts, not long after the monks came in 1946. The nearby village of Garvald was cut off by snow and no provisions could get in. In those early days these strange men in their hoods and medieval robes had been an unnerving presence and there was suspicion and fear. Then, as the hamlet gathered itself for a winter of hardship and scarcity, the monks came down from the abbey bringing with them the bounty of the land, provisions in abundance and no little expertise in the ways of making mechanical things work.

The misunderstanding vanished and the monks now occupy a special place in the heart of the village.

So how do you begin to explain even the concept of prayer in a society which has deemed entreaty to the Creator as obsolete? Even among many of us who believe in these things prayer is a resource you turn to only in extremis; in mortal peril and when your team is looking for an equaliser in the last minute. To those who have no religious belief it is merely the hallmark of an older age of superstition and ignorance.

But I recognise that even among my atheist friends there is occasionally an acknowledgment of things beyond human comprehension and an admission of the possibility of design in beauty. That some thanks and praise may be due to someone does not seem to be entirely unreasonable in the circumstances.

Nunraw welcomes people of all faiths and none. ‘Of course many Catholics come here to stay a few days but so also do Protestants, Jewish people, Muslims and Hindus and people with no faith,’ says Father Mark. ‘We do not preach at them or seek to convert them. They can do as much or as little as they please. We just ask that they respect the spirit of this place. And if they take something away with them and it helps them, as it often seems to do, then we feel that a purpose is being served.’

Several of the other monks venture something of what brought them here and the lives they left behind: of running boats up and down the West African coast; of carefree days among alcohol and girls at university. And there is Father Aelred from Tyneside, who has twice left the community, but on each occasion felt compelled to return. He says: ‘I was attracted to the idea of monasticism but wasn’t leading the type of life conducive to it. I was seeing a girl for a while but I knew that I would only really be happy living this life.’

THEN behold Brother Philip. Approaching 90, he is the oldest member of the community but reminds you of a slightly older version of the actor Edward Fox. Gradually though, as he remembers a Geordie childhood, the elongated vowels of Tyneside emerge and, when he talks of his dad, a miner, the years roll away and he is mourning him anew.

The future is uncertain and each monk knows that, in a few years’ time, their community will simply cease to be unless some more men are called to join them. ‘We’ll leave that in the hands of God,’ says Father Mark.

Already, though, a subtle shift in policy has occurred. Once they would only have received men in their 20s and 30s, now they are open to older inductees, or novices, as they are termed.

Brother Michael is one of these. He is at the start of a five-year journey which will hopefully see him become a full member of the Nunraw community. He is a Glaswegian in his mid-50s who recently retired after 37 years with HMRC.

‘I have come here over the years to find silence and to escape the increasingly loud and meaningless noise of the world and to truly encounter God,’ he says. ‘I enjoyed my career and the many good people I worked with and I shall miss them and my family, but this is the place where I think I’m meant to live out the rest of my life.’

And you observe these men again and you ponder their relevance in the 21st century where we seem daily to be unlocking the secrets of the universe and discovering the sources of earthly happiness without the aid of The Almighty, thank you very much. And yet you wonder again at how we conspire to put these riches beyond the reach of many of our fellow humans.

And you wonder at how increasingly empty and unhappy your own life can seem even when you think you have it all. And you know that, for a day or so, you were given a glimpse of something that you once yearned for and you felt a momentary desire once more to cast off the world and its empty promises.

And you know, too, that deep within yourself you wouldn’t experience contentment like this any time soon unless, perhaps, you returned here. And you wonder why the very thought scares the hell out of you yet thrills you, too. And then you are thankful just for the knowledge that this place exists at all and that you will carry it with you in your heart for the rest of your days.

To discover more about the Nunraw monks, write to: Sancta Maria Abbey, Nunraw, Haddington, EH41 4LW. or telephone: 01620830223.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)