Posted: May 13, 2011 | Author: roy hamric | Filed under: buddhism, people, photography | Leave a comment:

Thomas Merton named this photograph “The Sky Hook,” but he wrote,

“It is the only known picture of God.” See my essayThomas Merton: Looking

Through the Window in the On the Record listing.

The Hameric Journal. https://royhamric.wordpress.com/?s=Thomas+Merton

https://royhamric.wordpress.com/?s=Thomas+Merton

Posted: May 13, 2015 | Author: roy hamric | Filed under: articles, buddhism, Buddhism Zen, states of mind, writing |Tags: Merton on

photography, thomas merton in

Asia | 1 Comment

Mount Kangchenjunga

from Darjeeling

Thomas Merton, during his Asian pilgrimage, waited for days to see and

photograph Mount Kanchenjunga, but it was covered by clouds. His visual sense

was acute. In Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, he wrote: “Nothing

resembles substance less than its shadow [words, drawings…]. To convey the

meaning of something substantial you have to use not a shadow but a sign, not

the imitation but the image. The image is a new and different reality, and of

course it does not convey an impression of some object, but the mind of the

subject: and that is something else again.” I discuss his pilgrimage and his

photography in an essay under “On the Record,” which is listed in the column on

the right. Merton died in Bangkok in December 1968.

Posted: May 13, 2011 | Author: roy hamric | Filed under: buddhism, people, photography | Leave a

Thomas Merton named this photograph “The Sky

Hook,” but he wrote, “It is the only known picture of God.” See my essayThomas

Merton: Looking Through the Window in the On the Record listing.

Thomas Merton named this photograph “The Sky

Hook,” but he wrote, “It is the only known picture of God.” See my essayThomas

Merton: Looking Through the Window in the On the Record listing.

Posted: May 15, 2010 | Author: roy hamric | Filed under: articles, buddhism, people, photography | 1 Comment

This is an expanded version of an essay that appeared in The Kyoto Journal, issue

No. 47 in 2001.

The Photography of Thomas Merton: Seeing Through the Window

By Roy Hamric

Trappist Monk Thomas Merton, in his twenty-seventh year at Gethsemani

Monastery, wrote to his friend novelist John Howard Griffin, in 1968, shortly

after he received the gift of a camera: “It is fabulous. What a joy of a

thing to work with.The camera is the most eager and helpful of all

beings, all full of happy suggestions. Reminding me of things I have

overlooked and cooperating in the creation of new worlds. So Simply. This

is a Zen camera.”

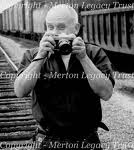

merton with his Canon

And so, Merton’s life as an amateur photographer intensified. One of the

most spiritual and literary men of our times, Merton had been taking

photographs of his friends and the surroundings at Gethsemani, near Louisville,

Kentucky, for several years. He enjoyed using the clear glass of the camera

lens and the frame of the viewfinder as tools to help him see and to understand

the world. The mirror-like view of the camera, recreating whatever it is

pointed at, was perfect for Merton’s practical blend of spirituality.

His spiritual path had evolved over the years, as he began to explore

the spiritual connections with Zen, largely through the writings of D.T.

Suzuki. He longed to become more deeply involved in the “ordinary.”

merton in a baseball

cap

Many of Merton’s earliest photographs are similar in style to early

Chinese painter-calligraphers who tried to capture the direct essence of form.

Merton wrote to his friend, John C. H. Wu, the translator of one of the best

English versions of the Tao Te Ching, that he was uncomfortable with “mystical

writings.” He expressed his desire to go to Asia “to seek at the sources some

of the things I see to be so vitally important–the Zen ground of all the

dimensions of expression and mystery in the brushwork of Chinese calligraphy-

painting, poetry and so forth.”

“On the contrary,” he wrote, “it seems to me that mysticism flourishes

most purely right in the middle of the ordinary. And such mysticism, in

order to flourish, must be quite prompt to renounce all apparent claim to be

mystical at all.”

It is no surprise that a monk who lived a life sequestered from society

should be attracted to the still, and silent, photographic image. Within

that visual stillness and exchange between the seer and the seen lies a

mystery–perhaps some of the spiritual mystery of why one would become a monk in

the first place.

During the sixities, as Merton began to explore Asian philosophy, he

also began to experiment with calligraphy, creating striking images. In

1958, he wrote in his journal that he had bought a copy of “The Family of

Man,” Edward Steichen’s landmark photography book which established

the power of photography to evoke universal truths. Merton saw the images as a

form of “writing” in which “no explanations are necessary!” “How scandalized

some would be if I said that this whole book is to me a picture of Christ, and

yet that is the Truth..” This reaction to the visual came in the same entry in

his journal in which he recorded what was later to be described as his

“Louisville epiphany,” wherein he wrote that he had experienced an

overwhelming sense of “oneness” with other people on a street corner.

John Howard Griffin, the author of the civil rights classic Black

Like Me, was also an amateur photographer. In 1963, he wanted to

build a photographic archive of Merton and his life at Gethsmeni. He wrote to

Merton mentioning his desire, and he visited him a short while later. While

there, he said, “Tom watched with interest and wanted an explanation of the

cameras––a Leica and Alpha.” Merton told Griffin, “I don’t know anything about

photography, but it fascinates me.”

Merton had begun his first serious exploration of photography when in

January 1962, he visited a Shaker village near the monastery. He found “some

marvelous subjects,” he wrote in his journal, and his description of what he

saw and photographed signaled that his search for subjects was part of a highly

developed visual acuity that unfolded in a charged contemplative state of mind

: “Marvelous, silent, vast spaces around the old buildings.” he wrote in his

journal. “Cold, pure light, and some grand trees…. How the blank side of a

frame house can be so completely beautiful I cannot imagine. A completely

miraculous achievement of forms.”

Merton and Griffin started a spiritual-literary friendship during a

retreat Griffin made at Gethsemani. Griffin sensed that Merton’s mind innately

took to the camera’s frame. He served as a constant source of

encouragement to Merton, volunteered to process Merton’s film and became a

casual critic of his contact sheets.

They exchanged regular letters touching on Merton’s photography from

1965 through 1968–the year of Merton’s accidental death in Bangkok, following

his epiphanic tour of Asia. Merton’s Asian journal of his

pilgrimage, and the inclusion of about 30 photographs that he took during the

trip, were published as The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton–a work

unlike Merton’s other books in its personal intensity. Upon finishing the book,

you have a sense that Merton’s life was in a profound stage of evolution.

That revelation, for me, comes through most strongly in the journal

entries chronicling the things he photographed during his journey.

But his earlier photographs also offer tantalizing clues to Merton’s

spiritual journey in his final years.

By 1964, Merton had regular access to a camera and his reading of Zen

books became an integral part of his life, no doubt stimulating his interest in

the visual experience itself through its emphasis on “attention” and

“experiencing the moment.” On September 24, Merton linked Zen and photography

in another journal entry: “After dinner I was distracted by the dream camera,

and instead of seriously reading the Zen anthology I got from the Louisville

Library, kept seeing curious things to shoot, especially a window in the tool

room of the woodshed. The whole place is full of fantastic and strange

subjects––a mine of Zen photography.”

In the following years, he moved on to better cameras, eventually

gaining access to a Rollieflex owned by the monastery. When it

malfunctioned in 1968, he immediately wrote to Griffin, who sent him a 35mm

Canon FX with 50 mm and 100 mm lenses.

The new camera was the springboard to more sophisticated pictures, and

Merton was soon comparing notes with Griffin on the ins-and-outs of

photography. He never took any interest in developing his own film or printing

his images, instead sending exposed rolls of film to Griffin, who with his son,

Gregory, developed the film and sent back contact prints for Merton to select

the images he wanted printed. Griffin recalls that he and his son were often

frustrated that Merton seemingly skipped over “superlative” images and instead

marked others that seemed ordinary to them.

“He went right on marking what he wanted rather than what we thought he

should want,” recalled Griffin. “ Then, as he keep taking photographs, more and

more often he would send a contact sheet with a frame marked and an excited

notation: ‘At last––this is what I have been aiming for.”

Griffin soon began to appreciate Merton’s personal visual quest: “He

focused on the images in his contemplation, as they were and not as he wanted

them to be. He took his camera on his walks and, with his special way of

seeing, photographed what moved or excited him––whatsoever responded to that

inner orientation.”

Merton’s interest in painting and photography had taken a decisive turn

in early 1965, after he read “The Tao of Painting” by Mai-Mai Sze, a

work he called “deep and contemplative.” He began practicing Chinese

brushstrokes in a freehand style, one of which he published on the cover

of Raids on the Unspeakable. In August of that year, he

moved to a cottage hermitage surrounded by woods on the grounds of Gethsemani

where he found more solitude and where nature increased his awareness of flora

and fauna. Writing in his journal of his early days at the hermitage, he said

the hermitage lifestyle challenged him “to see the great seriousness of what I

am about to do.”

“Contrary to all that is said about it,” he wrote, “I do not see how the

really solitary life can tolerate illusion or self-deception. It seems to

me that solitude rips off all the masks and all the disguises. It

tolerates no lies. Everything but straight and direct affirmation, or silence,

is mocked and judged by the silence of the forest.”

Merton’s natural visual acuteness was intensified during his walks

through the fields and woods at his monastery. As a band of deer appeared from

out of the woods one day, he watched silently:

“I watched their beautiful running, their grazing,” he wrote in his

journal. “Every movement was completely lovely, but there is a kind of

gaucheness about them sometimes that makes them even lovelier, like girls. The

thing that struck me most–when you look at them directly and in movement–you

see what the primitive cave painters saw. Something you never see in a

photograph. It is most awe-inspiring. The ‘spirit’ is shown in the

running of the deer. The deerness that sums up everything and is sacred

and marvelous.”

Merton described such deep perceptions as “contemplative intuition, yet

this is perfectly ordinary, everyday seeing–what everybody ought to see all the

time.”

“The deer reveals to me something essential, not only in itself, but also

in myself,” he wrote. “Something beyond the trivialities of my everyday

being, my individual existence. Something profound. The face of that

which is both in the deer and in myself.”

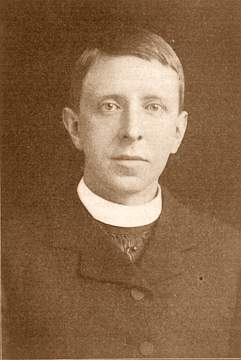

thomas merton

Whenever Griffin visited Merton, the two men often took long walks in

the woods and surrounding countryside looking for objects and scenes to

photograph. A letter dated Dec. 12, 1966, refers to pictures Merton took of

tree roots. “I signed them as you requested, and have sent back the ones you

want,” he wrote to Griffin. “They are really splendid. I find myself

wondering if I took such pictures.”

His life at Gethsemani was isolated, yet he became friends with another

most unusual photographer, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, who had photographed Merton

and who lived in Louisville. Meatyard had already achieved great recognition as

an exceptionally original and brilliant photographer. He was also interested in

Zen, and he took many mysterious, haunting photographs of Merton. They

exchanged 16 letters. Meatyard was not, unlike most people, awed by Merton’s

reputation, and he seemed to see the man whole: “[I was] photographing a

Kierkegaard who was a fan of Mad [magazine]; a Zen adept and hermit who droooled

over hospital nurses with a cute behind…a man of accomplished self-descipline

who sometimes acted like a 10 year old with an unlimited charge account at a

candy store.”

One of Merton’s most

personal photographs from that period is called “The Sky Hook.” He wrote

that the picture “is the only known photograph of God.” The picture’s

composition is balanced between material and non-material space, cut through

the center from the top by a steel hook, curled toward the sky–empty–holding

nothing.